On Sunday, November 16, 2014 officials from the Drug Enforcement Agency met the medical staff of at least three NFL teams (the Seattle Seahawks, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the San Francisco 49ers) for surprise inspections after their games.[1] The inspection arose out of a suspicion that the teams were in violation of the Controlled Substances Act by illegally dispensing painkillers to players to treat their career-related pain and prolong their playing time.

No arrests were made and NFL Spokesman, Brian McCarthy, reported complete cooperation with the DEA and said that “no irregularities were found.†The inspection consisted of interviews with team physicians and requests for documentation for any controlled substances in their possession, as well as bag-searches.

The suspicions fueling the investigation were based on a lawsuit involving over 1,200 retired players, many of whom go back to 1968.[2] The suit alleged that the NFL intentionally, and with no regard for the welfare of their players, illegally distributed painkillers to prolong careers, leaving many with a legacy of addiction, physical deterioration and mental illness once their careers were over. Violations going back as far as 2009 are subject to legal penalty under the five-year statute of limitations.

A U.S. District judge dismissed the class-action lawsuit just over a month after the raids, on December 17. In the ruling, Judge William Alsup affirmed the NFL\’s position that the players were already protected by federal labor laws and the collective bargaining agreement between the league and players.[3]

NFL’s History of Painkiller Abuse

The list of former NFL players, trainers, doctors and team officials chronicling a culture of rampant painkiller distribution and abuse is quite lengthy. The brutal nature of the sport, coupled with the short shelf-life of athletes in the league makes the stories of players doing “anything to stay on the field†quite plausible. For many players, the decision was take painkillers to stay on the field, or ask questions and see someone else take your spot on the team.

The list of former NFL players, trainers, doctors and team officials chronicling a culture of rampant painkiller distribution and abuse is quite lengthy. The brutal nature of the sport, coupled with the short shelf-life of athletes in the league makes the stories of players doing “anything to stay on the field†quite plausible. For many players, the decision was take painkillers to stay on the field, or ask questions and see someone else take your spot on the team.

NFL veterans describe a “Wild West†type atmosphere in the 80\’s, where players lined up outside of trainers\’ rooms waiting for a shot to numb pain, or plane rides where trainers would walk down the aisles and hand out Vicodin pills like Tic Tacs.[4] The end result was often addiction that followed them well beyond their playing days, in addition to a host of other health problems.

A 2011 study conducted by Washington University in St. Louis, makes these scenarios sound even more believable. The results revealed some disturbing numbers.[5]

- NFL players misuse opioid pain medications at a rate four times that of the general population.

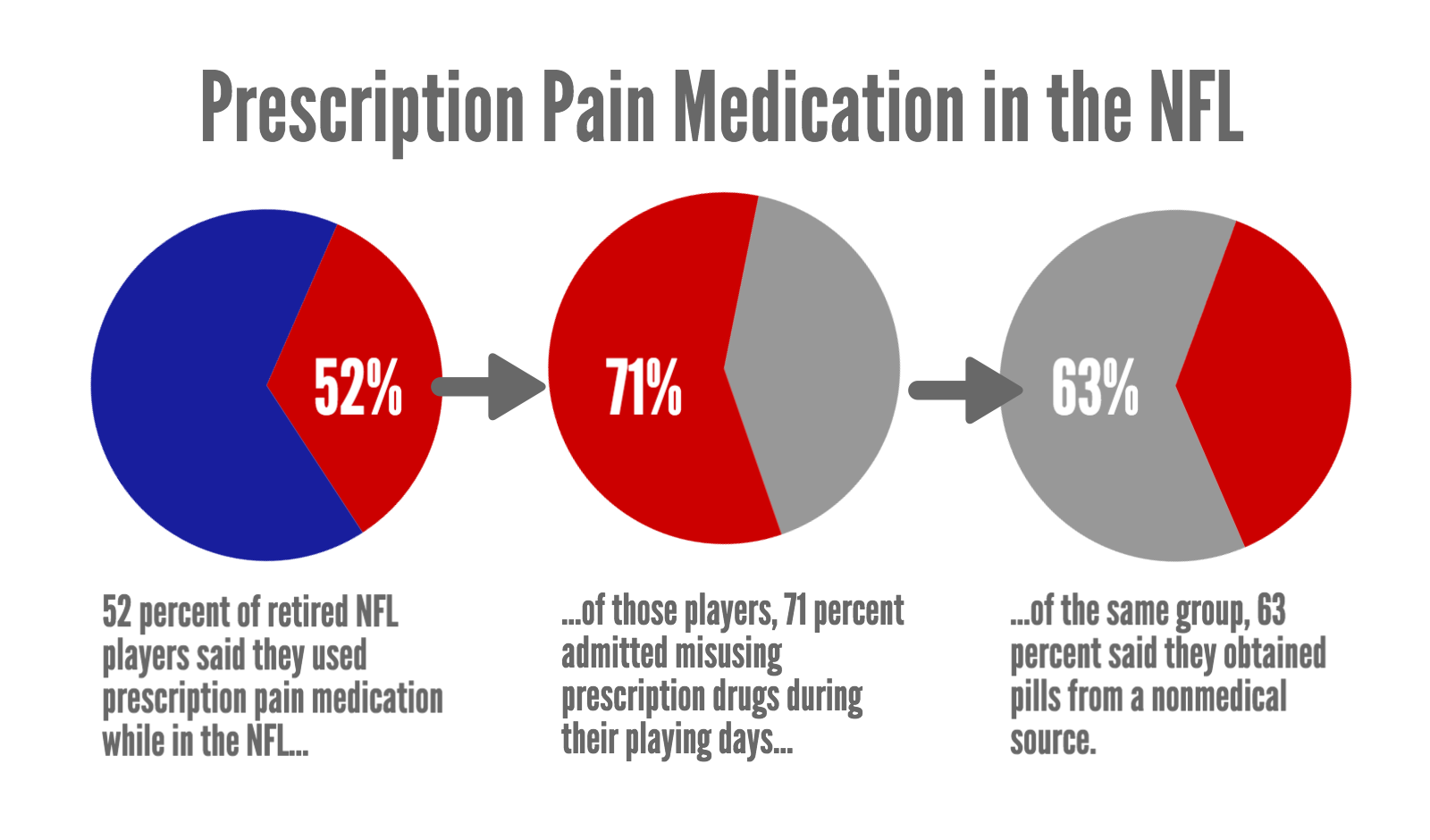

- 52 percent of retired NFL players said they used prescription pain medication while in the NFL.

- Of those players, 71 percent admitted misusing prescription drugs during their playing days; of the same group, 63 percent said they obtained pills from a nonmedical source; meaning a teammate, coach, trainer, family member or street dealer.

- 15 percent of prescription drug misusers admitted to misusing medication within the last 30 days.

A Litany of Post-Career Health Issues

At the very least, the recently dismissed lawsuit highlights the decrepit physical and mental health of once proud, big and strong retired professional football players. The NFL has proven to be a chew you up and spit you out league for a large majority of players who\’ve struggle with everyday life following their playing days.

Aside from marital and financial difficulties, a large portion of retired NFL athletes are followed by lingering injuries well beyond their playing days. A Newsday survey of 763 former professional football players highlights this.[6]

- 61 percent of former players said they found it difficult to adjust to everyday life following their career.

- 42 percent said injuries from their playing days have been the biggest challenge in retirement.

- 70 percent of retired players surveyed said they\’re still affected by knee injuries, 67 percent are dogged by lower back injuries, 65 percent are battling shoulder pain, 56 percent deal with neck issues and 49 percent have lingering head injuries.

Since 2006, 12 former or active NFL athletes have committed suicide, with 10 coming since 2010. Autopsies performed on many of the former NFL players revealed brain damage, most famously on former all-pro, Junior Seau, according to the National Institute of Health.

Based on research presented at the 65th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, about 40% of players with a history of concussions also have mild to moderate symptoms of depression. This rate of depression is nearly three times higher than that of the general public.[7]

Researchers from the Department of Veterans Affairs\’ brain repository examined the brain tissue of 128 former football players and found that 101 of them tested positive for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Clearly, NFL athletes are not only at serious health risk during their playing days, they continue to be at risk for years after.[8]

Who Is to Blame and What Can Be Done?

While 85 percent of the players interviewed by Newsday believed that the NFL did not adequately prepare them for life after football, 89 percent said that despite the health difficulties, they\’d do it all over again. Determining who is at fault is not as easy as pointing fingers.

A simple solution would seem to be to expand playing rosters so players would not have to experience so much pain during and after their careers. But a diluted on-field product is the likely result of roster expansion, ultimately leading to diminished public interest. So in a sense, painkillers in the NFL are used as performance enabling drugs that allow the games to be played at the highest levels.

Proper education is the best remedy for coaches, trainers, doctors and athletes. The medical industry is still learning how to healthily handle chronic pain injuries, with much of the nation still relying on pain medicine as the primary treatment.

Players also need to ask themselves how much their lives outside of football matter to them. Many athletes have retired earlier than expected, citing the desire to have a healthy post-playing life. Though it may be difficult to walk away from the potential money, it is something many may want to consider. Is playing an extra 2-3 years in your early 30s worth a lifetime of pain and compromised mobility, among other potential health difficulties?