A recent telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control revealed that 20 percent of all high school boys’ parents have been told they have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). With these diagnoses comes a new explosion in medication used to treat these conditions. Drugs such as Adderall, Ritalin and Concerta have long been used to treat ADHD. Since 1996, production of methylphenidate (the primary ingredient in Ritalin and Concerta) has increased 600%. Production of amphetamine, which is the active ingredient in Adderall increased 28 times.[1]

A recent telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control revealed that 20 percent of all high school boys’ parents have been told they have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). With these diagnoses comes a new explosion in medication used to treat these conditions. Drugs such as Adderall, Ritalin and Concerta have long been used to treat ADHD. Since 1996, production of methylphenidate (the primary ingredient in Ritalin and Concerta) has increased 600%. Production of amphetamine, which is the active ingredient in Adderall increased 28 times.[1]

The primary concern lies with how this explosion will affect young adults. Experts claim that while we have paid significant attention to the outbreak of prescription opiates plaguing the country, far less attention has been paid to the role of stimulants as gateway drugs.

ADHD is the most commonly diagnosed mental disorder in children, but it can also affect teens and adults. The condition is generally characterized by an inability to focus or pay attention for sustained periods of time. Children with the condition may also be hyperactive and unable to control impulses. It is often first detected in young, school-aged children, when it is determined that they can’t concentrate on the tasks put in front of them.

In adults, ADHD frequently leads to disorganization, difficulty with time management, relationship problems and an inability to set and achieve goals. It is also common for adults with ADHD to struggle with addiction.

Enormous Increases in ADHD Diagnoses and Prescriptions

There’s no question that the diagnoses of ADHD have exploded in recent years. It was not even recognized as a mental disorder in the American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 1968, when it was called hyperkinetic impulse disorder. After being officially termed ADHD in 1987, cases of the disorder began to rise, as did the amount of prescriptions.

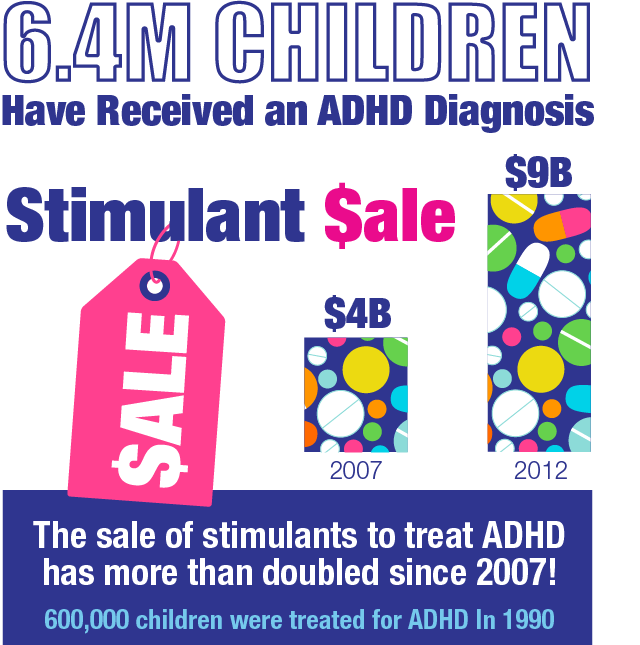

Numbers from the CDC showed that an estimated 6.4 million children, ages 4 – 17, had received an ADHD diagnosis at some point in their lives. This represents a 16 percent increase since 2007, and a 41 percent spike since 2003. The sale of stimulants to treat ADHD more than doubled to $9 billion in 2012, up from $4 billion in 2007.[2] As of 2010, one out of 10 American children of all ages had been diagnosed with ADHD, an increase of 22 percent from 2003. There were only 600,000 treated for ADHD in 1990, according to a Medscape article.

There are two ways to look at the dramatic increase in diagnoses and prescriptions. Some healthcare professionals argue that the rising diagnoses are a sign of better technology, more knowledge, higher recognition and a greater acceptance of the condition. Others argue that the growth in diagnoses and prescriptions are a result of parents reacting to advertisements by drug companies; and teachers, parents and doctors taking a popular shortcut to improve school performance.

With increased academic competition and immense pressure to be accepted into college, many parents are willing to do whatever it takes to give their child an edge. If parents know of prescription drugs that will improve their child’s academic performance, many will be tempted to pressure doctors into diagnosing ADHD and then getting necessary prescriptions.

“There’s no way that one in five high school boys has ADHD,” said Dr. James Swanson, one of the leading researchers in the field for more than two decades, in a New York Times interview. “If we start treating children who do not have the disorder with stimulants, a certain percentage are going to have problems that are predictable – some of them are going to end up with abuse and dependence.”

Subjective Observations Leading to Over-Diagnosis

How much of a child’s inability to focus in class and control their impulses is a function of a neurodevelopmental disorder or of just a kid being a kid? This is the question that educators, parents and mental health experts must grapple with. Long before the discovery of ADHD, countless children struggled with school performance, hyperactivity and impulsive behavior, and found ways to turn things around without the use of prescription drugs.

The rise in ADHD diagnoses and prescriptions in children is in some ways parallel the rise in chronic pain and subsequent medications for adults. Rather than taking the time to look for drug-free solutions, people are eager for immediate results and choose to rely on the availability and quick results of prescriptions. Many healthcare professionals worry that the diagnosis of ADHD comes down to opinions instead of concrete facts.

If parents know of prescription drugs that will improve their child’s academic performance, many will be tempted to pressure doctors into diagnosing ADHD and then getting necessary prescriptions.

The diagnostic criteria, which was updated in 2013 in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, is listed below. A diagnosis for children under the age of 12 requires the presence of six or more of the listed symptoms, each of which having persisted for at least six months “to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that negatively impacts directly on social and academic/occupational activities.” These symptoms must be present in two or more settings.

9 Inattentive Symptoms

- “Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, or during other activities (e.g. overlooks or misses details, work is inaccurate).”

- “Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g., has difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, or lengthy reading).”

- “Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (e.g., mind seems elsewhere, even in the absence of any obvious distraction).”

- “Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish school work, chores, or duties in the work place (e.g., starts tasks but quickly loses focus and is easily sidetracked).”

- “Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities (e.g., difficulty managing sequential tasks; difficulty keeping materials and belongings in order; messy, disorganized work; has poor time management; fails to meet deadlines).”

- “Often avoids or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g. schoolwork or homework; for older adolescents and adults, preparing reports, completing forms, reviewing lengthy papers).”

- “Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).”

- “Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli (e.g., for older adolescents and adults may include unrelated thoughts).”

- “Is often forgetful in daily activities (e.g., doing chores, running errands; for older adolescents and adults, returning calls, paying bills, keeping appointments).”

9 Hyperactive-Impulsive Symptoms

- “Often fidgets with or taps hands or squirms in seat.”

- “Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected (e.g., leaves his or her place in the classroom, in the office or other workplace, or in other situations that require remaining in place).”

- “Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is inappropriate (e.g., in adolescents or adults, may be limited to feeling restless).”

- “Often unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly.”

- “Is often “on the go” acting as if “driven by a motor” (e.g., is unable to be or is uncomfortable being still for extended time, as in restaurants, meetings; may be experienced by others as being restless or difficult to keep up with).”

- “Often talks excessively.”

- “Often blurts out answers before questions have been completed (e.g., completes people’s sentences; cannot wait for turn in conversation).”

- “Often has difficulty awaiting turn (e.g., while waiting in line).”

- “Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g. butts into conversations, games, or activities. May start using other people’s things without asking or receiving permission; for adolescents and adults, may intrude into or take over what others are doing).”

As can be seen, many of the symptomatic criteria required for a diagnosis are based on subjective observations. Terms such as “often,” and “excessively,” are impossible to universally measure -what may be seen as “often talking excessively,” to one person, may be perceived differently by another.

Promoting A Climate of Drug Dependency

Behavioral and mood disorders are clearly on the rise in America – and there are many cases where patients legitimately need medication in order to function normally. When thousands of children are taking antipsychotic medication before age 5, however, the potential for short and long-term health risk is unnecessarily high. Immediate side effects of the stimulants include loss of appetite, difficulty sleeping, mood swings, delayed growth and increased anxiety.

Behavioral and mood disorders are clearly on the rise in America – and there are many cases where patients legitimately need medication in order to function normally. When thousands of children are taking antipsychotic medication before age 5, however, the potential for short and long-term health risk is unnecessarily high. Immediate side effects of the stimulants include loss of appetite, difficulty sleeping, mood swings, delayed growth and increased anxiety.

There is limited knowledge into the long-term health effects of stimulant use by children. There have been reports of children having suicidal thoughts, dramatic personality changes, and being more susceptible to illegal drug use.

Regardless of the long-term health implications, a problem exists when the knee jerk reaction for any condition is drug use. The cycle of immediately seeking drugs for any mental or physical condition must be broken. There are drug-free alternatives to treating ADHD, which may be effective for specific cases and should always be utilized before seeking medication and continued while using medication.[3]